General considerations

Steve Roberts

The following considerations should be applied to the majority of blocks described hereafter.

When performing these techniques it should always be remembered that a strong knowledge of anatomy is essential, that you need to be appropriately trained, and that the correct equipment and assistance must be available. Ultrasound is operator dependent.

Pre-operative

- Prior to meeting the patient, understand the extent of the surgery being planned and the consequent length of analgesia required.

- Generally the more peripheral a block is – the better the risk-benefit balance. And thus more acceptable to the patient and parents/carers.

- If prolonged analgesia is required due to the amount of surgical trauma, or to facilitate physiotherapy then a catheter technique should be considered;

- If you are considering a catheter technique give thought to where the patient will be nursed, often catheter techniques can only be nursed on specific wards. Don’t offer something that cannot be delivered.

History

- In particular looking to identify potential contraindications to regional anaesthesia (local anaesthetic allergy, anticoagulation).

- Identify pathology that may make a technique difficult or impossible e.g. spina bifida or scoliosis.

- Discuss patient’s experiences with previous regional anaesthetic techniques.

- A Pain history is important because some patients e.g. those with developmental delay may find it difficult to express their pain. How well do they cope with pain? How do they show their discomfort? A chronic pain history should highlight the possibilities of difficulties with post operative pain management; a catheter technique may be beneficial in these patients.

- Drug history: analgesics, anticoagulants, baclofen. Patients on baclofen undergoing orthopaedic procedures may be at increased risk of muscle spasm post operatively, consider a catheter technique.

Examination

- If possible check the proposed injection site.

- If feasible assess and document neurology of patients with known neuromuscular conditions.

- Make a note of patient’s weight so maximum local anaesthetic dose can be calculated.

Consultation

- At all times during the consultation a realistic description of success and post op course should be given. This should include what will happen should the original planned analgesia fail. Manage expectations.

- Discuss with patient and carers options for analgesia covering both benefits and risks.

- If possible explain to patient how their limb will feel post operatively, ‘like pins and needles when you fall asleep on your arm’. Children can become quite anxious in recovery as a consequence of the paraesthesiae.

- In older children having minor surgery the operation may be done awake; have EMLA applied to the block injection site (you may wish to scan the patient on the ward prior to this). If a parent/carer is going to attend ensure they know what their job is in the anaesthetic room i.e. distracting their child during the proceedings. Ensure a nurse will be attending the procedure to support both the patient and the parent/carer.

Anaesthetic Room

- Full and appropriate monitoring is assumed throughout the website.

- Intravenous access and airway both secured.

- If prophylactic antibiotics indicated for surgery then administer it pre-block.

- Position patient safely in block position.

- Assess surface anatomy.

- Position your ultrasound machine such that you can clearly see it without turning your head.

ERGONOMICS IS IMPORTANT.

Fig. Neonatal TAP block, operator, probe, patient and machine in alignment makes needling easier.

- Choose an appropriate probe.

Note that the majority of US probes are broadband arrays i.e. the frequency is chosen from within a given range.

A typical linear probe has a 10-5MHz frequency range or better, as such they are suitable for the majority of blocks in children. More modern probes will have higher frequencies of up to 15MHz.

The curvilinear probes are of lower frequency and are suited to deep needle placement e.g. a lumbar plexus or epidural scan in an adult.

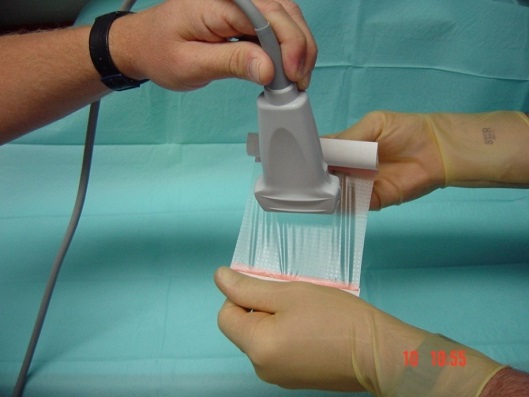

The second feature to consider when choosing a probe is the size of its footprint. This will depend on which block is being used and the size of the patient. Generally a hockey stick probe with a 25mm or less footprint is suited for blocks in children under 10kg or where access is limited e.g. the neck. - For single shot blocks – Wash hands and wear sterile gloves. Cover the probe directly with a transparent occlusive dressing such as an IV3000; you will need to pull the dressing taught over the probe so as not to allow any air to become trapped.

- For continuous catheter techniques – all central techniques require a full aseptic technique (mask, gown, gloves); it is probably also advisable for paravertebral (due to proximity to epidural space) and psoas blocks (a deep block, also bacteraemia has been reported post block). For more peripheral blocks it is debatable whether a gown is necessary. The probe should be placed in a sheath for all catheter techniques.

- Prep and drape the patient. This can be allowed to dry whilst you prepare the rest of the equipment. Ensure a large enough area of the patient is prepped and visible so that the length of the nerve can be scanned if necessary.

- For peripheral nerve blocks choose an appropriately long 18G regional anaesthetic needle. This depends on the expected depth of the target nerve (patient age and BMI), and whether an in plane or out of plane needling technique is deployed. The former entails inserting the needle 2-3 times further into the patient.

You should have 2 lengths available to your department, a 40 or 50mm and an 80-100mm length needle. This should cover most eventualities. All neonatal blocks can be performed with a 40-50mm needle; do not use a longer needle than necessary. - Ensure all the kit is flushed through, so that no air is present. If a catheter is used ensure this is patent prior to insertion.

If concerned about the amount of local anaesthetic available due to the small size of patient use saline for the flush. - Select which % local anaesthetic. Do not draw up more local anaesthetic than the maximum safe dose by weight.

Usually 0.25% levobupivacaine, ropivacaine or bupivacaine is used.

Use 0.125% levobupivacaine if there is concern regarding compartment syndrome or in neonates where there is concern regarding local anaesthetic toxicity.

Use 0.5% levobupivacaine, ropivacaine or bupivacaine for orthopaedic surgery where there is a high risk of muscle spasm post op e.g. multiple lower limb tendon transfers in cerebral palsy patient on baclofen. - Now set up the ultrasound machine.

Choose the highest frequency appropriate for estimated depth of the block.

Some machines allow you to opt for a ‘nerve’ setting thus optimising the image.

Select a depth greater than you expect to find the target nerve.

Ensure the gain is optimised. This is done by ensuring any vessels are black i.e. anechoic, and that the screen as a whole is a uniform grey. - It is useful for the needle to have an extension to connect it to the syringe.

- Orientate probe and image; most manufacturers have a tag on the screen to indicate which side of the probe is which. Alternatively touch one end of the probe

- Use adequate US gel to provide an air free interface

- A mapping or scout scan is performed to assess the anatomy, whilst scanning part of your hand should maintain contact with the patient to prevent the probe sliding off.

- To ensure correct orientation start scanning deeper than the expected target depth, then as the relevant bony and vascular landmarks are recognised decrease the depth until the target nerve of fascial layer is positioned in the middle of the screen.

- For in plane techniques the target should be moved to the side of the screen opposite to the needle entry point. This allows more time for the needle to be guided towards the target. Generally the needle should be inserted in as shallow a trajectory as is practically possible as this creates the best needle image. The needle should initially be aimed at the 6 o’clock position i.e. behind the nerve. After aspiration local anaesthetic is injected, if the nerve does not look to be surrounded then it may be necessary to withdraw the needle and aim at the 12 O’clock position i.e.

- For out of plane techniques the target should be in the middle of the screen, the needle is aimed at the 3 and/or 9 O’clock position i.e. either side of the nerve.

- If you lose the needle, immediately stop and check your probe and needle orientation. Use your probe to find the needle do NOT try to move your needle into the ultrasound beam.

- Some experts use PNS and US together. Whilst there is nothing inherently wrong with this beware of not identifying correct local anaesthetic spread and accepting a good motor response alone.

- Always aspirate prior to injection. In small children (<10kg) especially when learning use saline instead of local anaesthetic for you initial injection as this stops local anaesthetic being wasted due to poor needle position.

- The local anaesthetic should spread around the nerve – the ‘Doughnut sign’.

Intra operative management of block

- Ensure systemic analgesia given for procedures where the block does not cover visceral pain e.g. a rectus sheath block for pyloromyotomy.

- Observe changes in HR, BP and RR to provide information to assess any deficiencies in the regional anaesthetic technique employed.

- Consider avoiding anaesthetic agents that may obscure assessment of block success i.e. nitrous oxide and opiates. This is especially true when managing children with special needs as they can be very hard to assess in recovery.

- Consider systemic analgesic adjuvants e.g. magnesium is useful to give to cerebral palsy children under going reconstructive lower limb surgery

PACU / FIRST STAGE RECOVERY - It can be difficult to distinguish pain from emergence delirium or in fact just the displeasure of the paraesthesia. The help of an experienced recovery nurse and parent aids diagnosis.

- If there are doubts regarding analgesia consider giving a small fast acting opiate e.g. 0.25mcg/kg of fentanyl or 0.2-0.3mg.kg ketamine. If the block is effective the child will immediately settle.

- If doubts remain regarding the efficacy of your block it may be prudent (operation dependent) to prescribe a NCA/PCA just in case.

- All patients should be written up for alternative systemic analgesics as rescue analgesia.

COMMON ERRORS

- Failure to recognize maldistribution of LA, particularly when using PNS

- Orientation, every so often check your orientation, particularly during catherer insertions where the probe may have been put down and picked up again.

- Poor choice of needle-insertion site and angle

- Over insertion of needle due to poor needle visualisation, NEVER advance your needle if you don’t know where the tip is

Top Tips

- Generally it is best to teach yourself to scan with your non dominant hand

- Practice scanning techniques on yourselves and staff FIRST

- Practice needling techniques on phantoms FIRST

- Start with simple and familiar blocks in teenagers e.g. fore arm nerves or femoral nerve blocks

- If you can’t find the needle tip move the probe to find it – don’t move the needle.

- Consider using a Peripheral Nerve Stimulator until you master US

- Use the highest frequency available for the depth of target in tissues

- For children less than 10kg consider using saline to assess initial spread and as such needle position. This avoids wasting limited local anaesthetic in the wrong place.

- REMEMBER Ultrasound Guided Regional Anaesthesia is only as good as the operator