Guidelines Archive

Emergency care

Management of a Patient with Suspected Anaphylaxis During Anaesthesia

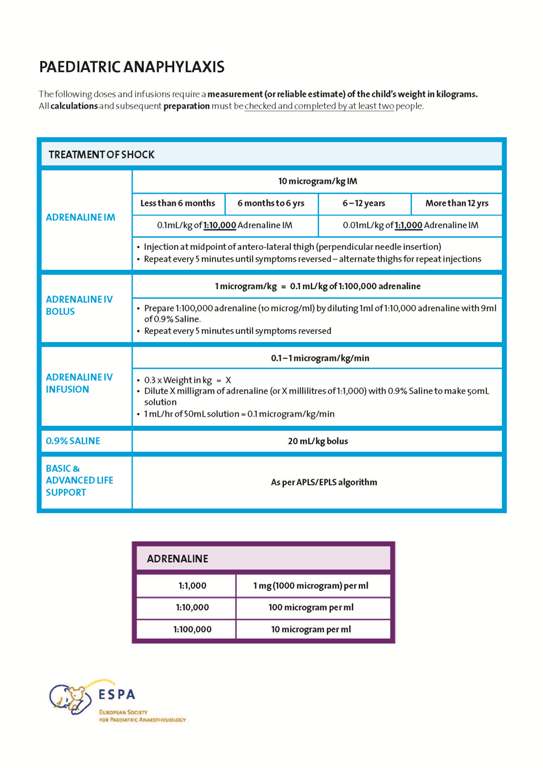

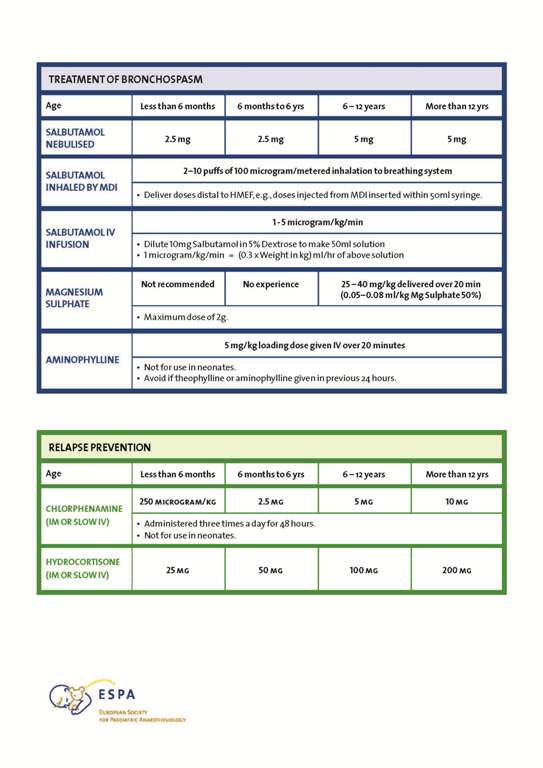

This two page Safety Drill includes the immediate and secondary management of adults and children who develop anaphylaxis. Drug dosages are included. The Safety Drill is easy to laminate and have available wherever children are anaesthetised.

The ESPA Action Card for this emergency is also included.

Link to the guideline: TBA

See below an example of the ESPA Action Card for the management of Anaphylaxis:

Fasting guidelines

Summary

Pediatric anesthetic guidelines for the management of preoperative fasting of clear fluids are currently 2 hours. The traditional 2 hours clear fluid fasting time was recommended to decrease the risk of pulmonary aspiration and is not in keeping with current literature. It appears that a liberalized clear fluid fasting regime does not affect the incidence of pulmonary aspiration and in those who do aspirate, the sequelae are not usually severe or long‐lasting. With a 2‐hour clear fasting policy, the literature suggests that this translates into 6‐7 hours actual duration of fasting with several studies up to 15 hours. Fasting for prolonged periods increases thirst and irritability and results in detrimental physiological and metabolic effects. With a 1‐hour clear fluid policy, there is no increased risk of pulmonary aspiration and studies demonstrate the stomach is empty. There is less nausea and vomiting, thirst, hunger, and anxiety, if allowed a drink closer to surgery. Children appear more comfortable, better behaved and possibly more compliant. In children less than 36 months this has positive physiological and metabolic effects. It is practical to allow children to drink until 1 hour prior to anesthesia on the day of surgery. In this joint consensus statement, the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, the European Society for Paediatric Anaesthesiology, and L’Association Des Anesthésistes‐Réanimateurs Pédiatriques d’Expression Française agree that, based on the current convincing evidence base, unless there is a clear contraindication, it is safe and recommended for all children able to take clear fluids, to be allowed and encouraged to have them up to 1 hour before elective general anesthesia.

1 BACKGROUND

Pediatric anesthetic guidelines for the management of preoperative fasting of clear fluids are currently 2 hours.1 The traditional 2‐hour clear fluid fasting time was recommended to decrease the risk of pulmonary aspiration and is not in keeping with current literature. It is based on historical adult literature2, 3 that may not be applicable to the pediatric population. Mendelson’s landmark paper showed a mortality effect in the obstetric population if they aspirated solid material, but there were no long‐term sequelae in those who aspirated clear fluid.

Pulmonary aspiration is a rare event in children, with an incidence of 0.07%‐0.1%.3–8 The recent APRICOT9 study found an incidence of 9.3/10 000 = 00.093%. The latter of course, included emergency and unfasted patients as well as elective children.

It appears that a liberalized clear fluid fasting regime does not affect the incidence of pulmonary aspiration,10, 11 and in those who do aspirate, the sequelae are not usually severe or long‐lasting.4, 7 Aspiration was cited as being responsible for 2% of cardiac arrests in the POCA II registry which of course included emergency and unfasted patients.12

With a 2‐hour clear fluids fasting policy, the literature suggests that this translates into 6‐7 hours actual duration of fasting10–17 with several studies up to 15 hours.18, 19 Fasting for prolonged periods increases thirst and irritability20 and results in detrimental physiological and metabolic effects.13, 21

The aim of developing these guidelines was to provide current evidence on perioperative fasting of clear fluids for elective surgery, minimize side effects of fasting while balancing against the risk of aspiration of gastric contents in the perioperative period and to provide a consensus statement on clear fluids fasting guidelines (Figure 1).

Figure 1

For these guidelines, the clear fluids are defined as water, clear (nonopaque) fruit juice or squash/cordial, ready diluted drinks, and nonfizzy sports drinks. Non‐thickened, non‐carbonated. The recommended maximum volume of clear fluids is 3 mL/kg.

2 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR GOOD CLINICAL PRACTICE

- Clear fluid fasting times for elective general anesthesia and sedation can be reduced to 1 hour, unless clinically contraindicated (Table 1)

Table 1. Preoperative fasting for elective procedures in children Age (y) Solid food, Formula milk Breast milk Clear fluids 0‐16 6 h 4 h 1 h - Contraindications that should be decided on by the anaesthetist and/or the surgical team are: Gastro‐oesophageal reflux (GORD) (either on treatment or under investigation), renal failure, severe cerebral palsy, some enteropathies, oesophageal strictures, achalasia, diabetes mellitus with gastroparesis, and/or surgical contra‐indications.

2.1 What is the supportive evidence for this recommendation?

A literature search of electronic databases PubMed, Medline, and Embase (publication dates up to October 14, 2017) was performed using the following MeSH terms: preoperative fasting in child, early intake oral carbohydrates, gastric emptying. Additionally, previous guidelines were used (AAGBI, ESA). From the references retrieved (PubMed 1507, Medline 100, Embase 584), the most recent and important articles were used.

Water empties from the stomach within 30 minutes22 and other clear fluids are almost gone within an hour.23 Studies demonstrate there is no difference in gastric volume or pH if children are starved 1 or 2 hours of clear fluids.24 If the clear fluids contain glucose, gastric emptying can be significantly quicker.25 A meta‐analysis of 1457 patients demonstrates that age was not a determinant of gastric emptying26.

Adverse outcomes may not be related to fasting status.27 Liberalizing clear fluid intake has been demonstrated to have a similar risk of pulmonary aspiration10 with no increase in morbidity or mortality and may not be related to fasting status.9 In the most recent multicentre pan‐European study, APRICOT, no episodes of admission to intensive care was registered due to aspiration.9

Several studies have shown less nausea and vomiting, thirst, hunger, and anxiety, if allowed a drink closer to surgery. Children appear more comfortable, better behaved, and possibly more compliant.28–30 It has also been demonstrated that allowing a drink closer to surgery in children less than 36 months has positive physiological and metabolic effects.13

2.2 Why 1 hour?

The evidence suggests that clear fluids are cleared to a gastric volume of 1 mL/kg after 1 hour.23 In institutions with a very liberal clear fluid fasting policy10 where children are allowed to drink until they come to theatre, the average fasting time was greater than 1 hour with no increased risk of aspiration. In this specific study, it was noted that no one was anesthetized within 30 minutes of a clear fluid drink. At another large institution, the clear fluid times were reduced to 1 hour in order to avoid the logistics and uncertainty that parents may face at home.11 This appeared a practical way to reduce fasting times and again did not increase the risk of aspiration.

2.3 How much clear fluid should we allow children to drink?

We would suggest that 3 mL/kg or smaller would be a good starting point. Through serial magnetic resonance imaging of gastric volume 3 mL/kg of sugared fluid, residual gastric volume was back to baseline values 1 hour after ingestion.23 Small amounts of clear fluid can and should be offered to the child up to 1 hour prior to the induction of general anesthesia while awaiting surgery21. One practical way is to offer 3 mL/kg of clear fluid to a child before being weighed by banding children according to their predicted weight.11 This would mean 1‐ to 5‐year olds are allowed up to 55 mL, 6‐12 years up to 140 mL, and greater than 12 years up to 250 mL. Such banding avoids the need to wait for a current weight (if it is unknown) that could delay the offer of an appropriate volume.

3 SUMMARY

The main benefits of updating current guidelines are:

- To avoid unnecessary prolonged clear fasting with the current 2‐hour guidelines and the side effects of this.

- To maintain a low incidence of pulmonary aspiration by maintaining high standards of anesthesia and avoiding reduced fasting in those children deemed high risk.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

No ethics approval was necessary.

DISCLOSURES

Dr Ehrenfried Schindler was past president for the European Society of Pediatric Anesthesia. Dr Mark Thomas is the section editor for Pediatric Anesthesia. The consensus statement has been endorsed by the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, European Society for Paediatric Anaesthesiology, and L’Association Des Anesthésistes‐Réanimateurs Pédiatriques d’Expression Française (Figure 1).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the council of the APAGBI and the ExBo of ESPA for considered feedback and discussion.

References

- 1 American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. Practice Guidelines for Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration: application to Healthy Patients Undergoing Elective Procedures. Anesthesiology. 2011; 114: 495‐ 511.

- 2Mendelson C. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anaesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946; 52: 191‐ 205.

- 3Roberts R, Shirley M. Reducing the risk of acid aspiration during cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1974; 53: 859‐ 68.

- 4Kelly C, Walker R. Perioperative pulmonary aspiration is infrequent and low risk in pediatric anesthetic practice. Pediatr Anesth. 2015; 25: 36‐ 43.

- 5Tan Z, Lee S. Pulmonary aspiration under GA: a 13‐year audit in a tertiary pediatric unit. Pediatr Anesth. 2016; 26: 547‐ 552.

- 6Walker R. Pulmonary aspiration in pediatric anesthetic practice in the UK: a prospective survey of specialist centers over a one‐year period. Pediatr Anesth. 2013; 23: 702‐ 711.

- 7Warner M, Warner M, Warner D, Warner L, Warner E. Perioperative pulmonary aspiration in infants and children. Anesthes. 1999; 90: 66‐ 71.

- 8Borland L, Sereika S, Woelfel S, et al. Pulmonary aspiration in pediatric patients during general anaesthesia: incidence and outcome. J Clin Anesth. 1998; 10: 95‐ 102.

- 9Habre W, Disma N, Virag K, et al. Incidence of severe critical events in paediatric anaesthesia (APRICOT): a prospective multicentre observational study in 261 hospitals in Europe. Lancet. 2017; 5: 412‐ 425.

- 10Andersson H, Zaren B, Frykholm P. Low incidence of pulmonary aspiration in children allowed intake of clear fluids until called to the operating suite. Pediatr Anesth. 2015; 25: 770‐ 777.

- 11Newton R, Stuart G, Willdridge D, Thomas M. Using quality improvement methods to reduce clear fluid fasting times in children on the preoperative ward. Pediatr Anesth. 2017; 27: 793‐ 800.

- 12Bhanaker S, Ramamoorthy C, Geiduschek JM, et al. Anaesthesia‐related cardiac arrest in children: update from Pediatric Perioperative Cardiac Arrest Registry. Anesth Analg. 2007; 105: 344‐ 350.

- 13Denhardt N, Beck C, Huber D, et al. Optimized preoperative fasting times decrease ketone body concentration and stabilize mean arterial blood pressure during induction of anaesthesia in children younger than 36 months: a prospective observational cohort study. Pediatr Anesth. 2016; 26: 838‐ 843.

- 14Adenekan A. Perioperative blood glucose in a paediatric daycase facility: effects of fasting and maintenance fluid. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2014; 11: 317‐ 322.

- 15Brunet‐Wood K, Simons M, Evasiuk A, et al. Surgical fasting guidelines in children: are we putting them into practice? J Pediatr Surg. 2016; 51: 1298‐ 1302.

- 16Williams C, Johnson P, Guzzetta C, et al. Pediatric fasting times before surgical radiologic procedures: benchmarking institutional practices against national standards. J Pediatr Nurs. 2014; 29: 258‐ 267.

- 17Engelhardt T, Wilson G, Horne L, Weiss M, Schmitz A. Are you hungry? Are you thirsty? ‐ fasting times in elective outpatient pediatric patients. Pediatr Anesth. 2011; 21: 964‐ 968.

- 18Buller Y, Sims C. Prolonged fasting of children before anaesthesia is common in private practice. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2016; 44: 107‐ 110.

- 19Agegnehu W, Rukewe A, Bekele N, Stoffel M, Nicoh M, Zeberga J. Preoperative fasting times in elective surgical patients at a referral hospital in Botswana. Pan Afr Med J. 2016; 23: 102.

- 20Brady M, Kinn S, Ness V, O’Rourke K, Randhawa N, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for preventing perioperative complications in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;( 7): CD005285.

- 21Frykholm P, Schindler E, Sumpelmann R. Pre‐operative fasting in children. A review of the existing guidelines and recent developments. BJA. 2017; 1‐ 6.

- 22Okabe T, Terashima H, Sakamoto A. Determinants of liquid gastric emptying: comparisons between milk and isoclorically adjusted clear fluids. Br J Anaesth. 2015; 114: 77‐ 82.

- 23Schmitz A, Kellenberger C, Liamlahi R, Studhalter M, Weiss M. Gastric emptying after overnight fasting and clear fluid: a prospective investigation using serial magnetic resonance imaging in health children. Br J Anaesth. 2012; 108: 644‐ 647.

- 24Schmidt A, Buehler P, Seglias L, et al. Gastric pH and residual volume after 1 and 2 h fasting time for clear fluids in children. Br J Anaesth. 2015; 114: 477‐ 482.

- 25Malmud LS, Fisher RS, Knight LC, Knight LC, Rock E. Scintigraphic evaluation of gastric emptying. Semin Nucl Med. 1982; 12: 116‐ 125.

- 26Bonner JJ, Vajjah P, Abduljalil K, et al. Does age affect gastric emptying time? A model‐based meta‐analysis of data from premature neonates through to adults. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2015; 36: 245‐ 57.

- 27Beach ML, Cohen DM, Gallagher SM, Cravero JP. Major adverse events and relationship to nil per os status in pediatric sedation/anesthesia outside the operating room: a report of the pediatric sedation research consortium. Anesthesiology. 2016; 124: 80‐ 8.

- 28Schreiner MS, Triebwasser A, Keon TP. Ingestion of liquids compared with preoperative fasting in pediatric outpatients. Anesthesiology. 1990; 72: 593‐ 597.

- 29Castillo‐Zamora C, Castillo‐Peralta LA, Nava‐Ocampo AA. Randomised trial comparing overnight preoperative fasting Vs oral administration of apple juice at 06:00‐06:30 am in pediatric orthopaedic surgical patients. Pediatr Anesth. 2005; 15: 638‐ 642.

- 30Splinter W, Steward J, Muir J. The effect of preoperative apple juice on gastric contents, thirst and hunger in children. Can J Anaesth. 1989; 36: 55‐ 58.

Citing Literature

Number of times cited according to CrossRef: 25

- Ric Bergesio and Marlene Johnson, in Children Undergoing Surgery and Anesthesia, A Guide to Pediatric Anesthesia, 10.1007/978-3-030-19246-4_5, (115-134), (2019).

- Robert Sümpelmann, Karin Becke, Rolf Zander and Lars Witt, Perioperative fluid management in children, Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000727, 32, 3, (384-391), (2019).

- Ashley Scott and Gemma Timms, Premedication and management of concomitant therapy, Surgery (Oxford), 10.1016/j.mpsur.2019.05.007, (2019).

- C. Morrison and S. Wilmshurst, Postoperative vomiting in children, BJA Education, 10.1016/j.bjae.2019.05.006, (2019).

- Y. Hamonic, C. Robert, J. Chauvet, M. Bordes and K. Nouette-Gaulain, La consultation d’anesthésie en pédiatrie, Perfectionnement en Pédiatrie, 10.1016/j.perped.2019.07.007, (2019).

- E. Taillardat, S. Dahmani and G. Orliaguet, Anestesia del lactante y del niño, EMC – Anestesia-Reanimación, 10.1016/S1280-4703(19)42973-3, 45, 4, (1-31), (2019).

- Vinícius Caldeira Quintão, Marcella Marino Malavazzi Clemente, Pedro Paulo Vanzillotta and Ana Carolina Ortiz, Global trend on reducing clear fluids fasting time in children: declaration of the Pediatric Anesthesia Committee and the scenario in Brazil, Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology (English Edition), 10.1016/j.bjane.2019.06.001, (2019).

- Sarah Heikal, Lowri Bowen and Mark Thomas, Paediatric day-case surgery, Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine, 10.1016/j.mpaic.2019.03.005, (2019).

- Keira P. Mason and Neena Seth, Future of paediatric sedation: towards a unified goal of improving practice, British Journal of Anaesthesia, 10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.025, (2019).

- Nicola Disma, Mark Thomas, Arash Afshari, Francis Veyckemans and Stefan De Hert, Clear fluids fasting for elective paediatric anaesthesia, European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000914, 36, 3, (173-174), (2019).

- Rebecca Isserman, Elizabeth Elliott, Rajeev Subramanyam, Blair Kraus, Tori Sutherland, Chinonyerem Madu and Paul A. Stricker, Quality improvement project to reduce pediatric clear liquid fasting times prior to anesthesia, Pediatric Anesthesia, 29, 7, (698-704), (2019).

- Ben Turner, Clear fluids are the solution to the fasting drought. The SPANZA perspective, Pediatric Anesthesia, 29, 6, (659-659), (2019).

- Jerrold Lerman, Clear fluid fasting in children: Is 1 hour the answer?, Pediatric Anesthesia, 29, 4, (385-385), (2019).

- David Linscott, SPANZA endorses 1‐hour clear fluid fasting consensus statement, Pediatric Anesthesia, 29, 3, (292-292), (2019).

- Katyayani Katyayani, Bianca Tingle and Neena Seth, Sips for little lips—Letter to the editor, Pediatric Anesthesia, 29, 1, (106-106), (2018).

- C. R. Bailey, M. Ahuja, K. Bartholomew, S. Bew, L. Forbes, A. Lipp, J. Montgomery, K. Russon, O. Potparic and M. Stocker, Guidelines for day‐case surgery 2019, Anaesthesia, 74, 6, (778-792), (2019).

- M. Charlesworth and M. D. Wiles, Pre‐operative gastric ultrasound – should we look inside Schrödinger’s gut?, Anaesthesia, 74, 1, (109-112), (2018).

- W. J. Fawcett and M. Thomas, Pre‐operative fasting in adults and children: clinical practice and guidelines, Anaesthesia, 74, 1, (83-88), (2018).

- Vinicius Quintão, Marcella Malavazzi, Pedro Vanzillotta and Ana Carolina Ortiz, Tendência mundial de redução do tempo de jejum de líquidos claros em crianças: declaração do Comitê de Anestesia em Pediatria e o cenário no Brasil, Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology, 10.1016/j.bjan.2019.06.001, (2019).

- Christiane E. Beck, Lars Witt, Lisa Albrecht, Nils Dennhardt, Dietmar Böthig and Robert Sümpelmann, Ultrasound assessment of gastric emptying time after a standardised light breakfast in healthy children, European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000874, 35, 12, (937-941), (2018).

- Lionel Bouvet, Nicolas Bellier, Anne‐Charlotte Gagey‐Riegel, François‐Pierrick Desgranges, Dominique Chassard and Mathilde De Queiroz Siqueira, Ultrasound assessment of the prevalence of increased gastric contents and volume in elective pediatric patients: A prospective cohort study, Pediatric Anesthesia, 28, 10, (906-913), (2018).

- David Rosen, Jonathan Gamble and Clyde Matava, Canadian Pediatric Anesthesia Society statement on clear fluid fasting for elective pediatric anesthesia, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie, 10.1007/s12630-019-01382-z, (2019).

- Hanna Andersson and Peter Frykholm, Gastric content assessed with gastric ultrasound in paediatric patients prescribed a light breakfast prior to general anaesthesia: A prospective observational study, Pediatric Anesthesia, , (2019).

- Arwa Mohammed Al‐Robeye, Anna Nicole Barnard and Stephanie Bew, Thirsty work: Exploring children’s experiences of preoperative fasting, Pediatric Anesthesia, , (2019).

- Mark Dorrance and Michael Copp, Perioperative fasting: A review, Journal of Perioperative Practice, 10.1177/1750458919877591, (175045891987759), (2019).

Safety

Safe Management of Anaesthetic Related Equipment

Although this guideline also highlights UK management structures the principles are valid for all who use anaesthetic equipment. The main points of this guideline are summarized below.

- Safety, quality and performance considerations must be included in all equipment acquisition decisions.

- Each directorate should nominate one consultant with responsibility for equipment management. This Nominated Consultant should be a member of a Medical Devices Management Group, which reports directly to the Trust Board, and he or she should liaise closely with the Technical Servicing Manager.

- An inventory of all equipment, including donated equipment, must be held by the technical department for maintenance and replacement purposes.

- A planned preventative maintenance programme must be in place.

- There should be a policy to cope with equipment breakdown.

- A replacement programme which defines equipment life and correct disposal procedures should be in place.

- Purchase of new equipment should include wide consultation (especially involving users), and technical advice to ensure practicality, cost effectiveness and suitability for purpose.

- There must be a commissioning or acceptance procedure before any new equipment is put into use.

- All users must be trained in the use of all equipment that they may use.

- All adverse incidents arising from the use of equipment must be reported.

Treatment

The management of postoperative vomiting in children

This guideline investigates the causes of postoperative vomiting in children and summarises the efficacy of treatments used to prevent and treat this important cause of morbidity in children.